Japan

Practical Japanese Vocabulary

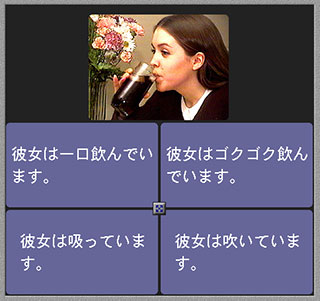

Today’s Rosetta Stone lesson could prove useful, in the right circumstances. Or perhaps it’s intended as a moral lesson…

Transcribed with pop-up furigana, the four sentences are:

彼女は一口飲んでいます。

彼女はゴクゴク飲んでいます。

彼女は吸っています。

彼女は吹いています。

上を向いて歩こう

Don’t ask me why…

上を向いて歩こう

上を向いて歩こう

涙がこぼれないように

思い出す 春の日

一人ぼっちの夜

上を向いて歩こう

にじんだ星をかぞえて

思い出す 夏の日

一人ぼっちの夜

幸せは 雲の上に

幸せは 空の上に

上を向いて歩こう

涙がこぼれないように

泣きながら 歩く

一人ぼっちの夜

思い出す 秋の日

一人ぼっちの夜

悲しみは 星のかげに

悲しみは 月のかげに

上を向いて歩こう

涙がこぼれないように

泣きながら 歩く

一人ぼっちの夜

一人ぼっちの夜

…but if you must know. [update: changed the link to a site with better romanization and translation]

Things that climb trees

Update 7/9/2005: based on today’s RS lesson, I’ve decided that I misunderstood noboru-koto in this context. I’m mulling it over, and will correct and update when I’ve sorted out “koto” more thoroughly; the romanization point stands, but my first example is incorrectly analogized to karumono, and incorrectly translated as well.

Steven den Beste went looking for the meaning of 「エルフを狩るモノたち」, which is written oddly, and has been romanized several different ways. By coincidence, my Rosetta Stone lesson this morning included the following phrases:

この動物は木に登ることもあります。

(roughly, "This animal, it's a thing-that-climbs in trees as well.")

よく飛ぶ動物はどれですか。

(roughly, "WhereWhich is the often-flying-animal?")

You won’t find 登ること as a single word in a dictionary, but if I were romanizing it, I would write “noboru-koto” instead of “noboru koto”. If I were referring to a group of cats (登ること達), I’d romanize it as “noboru-koto tachi”. I think that’s the clearest way to represent the meaning of the original.

You won’t find 飛ぶ動物 in a dictionary, either. This one definitely needs a hyphen, since “tobudoubutsu” is pretty unwieldy.

The anime title that started all this would ordinarily be written as 「エルフを狩る者達」. I think the simplest explanation for how it ended up being written was “the logo designer thought it looked cooler this way”.

[as for the which/where typo in the translation, I actually wrote that correctly the first time, then “corrected” myself. Proof that I shouldn’t blog in languages that I don’t speak fluently before I’m completely awake in the morningafternoon.]

Furigana-blogging

Every time I include some Japanese text in a blog entry, I’m torn between adding furigana and, well, not. It’s extremely useful for people who don’t read kanji well, but it’s tedious to do by hand in HTML. At the same time, I find myself wishing that my Rosetta Stone courseware included furigana, so that I could hover the mouse over a word and see the pronunciation instead of switching from kanji to kana mode and back. I’d also like to see their example phrases in a better font, at higher resolution.

80 lines of Perl later:

女の人は泳いでいます。

男の人は滑り落ちています。

男の子は転んでいます。

男の子は泳いでいます。

魚は泳いでいます。

鳥は飛んでいます。

雄牛は走っています。

鳥は泳いでいます。

[update: I tested this under IE on my Windows machine at work, and it correctly displayed the pop-up furigana, but ignored the CSS that highlighted the word it applied to; apparently my machine has extra magic installed, because the pop-up doesn’t use a Unicode font for some people. Sigh. Found! fixing tooltips in IE (about halfway down the page)]

Words to live by

I have a long way to go learning to read Japanese, but it’s nice to find the occasional phrase that my brain decodes automatically without stopping to translate:

いっぱい食べてオッパイ大きくしちゃいます!

The picture was cute, too.

Update: my, all of the online translation engines really make a hash of this one. I think BabelFish’s is the most glorious failure, though…

Reading and writing Japanese

The most obvious stumbling block for westerners learning Japanese (or Chinese, or Korean…) is the large number of seemingly indistinguishable symbols they’re written in. For Japanese, basic adult literacy requires 2,324. I’m about 10% of the way there, and have been for a while now.

I’m pretty good with the ones I know, enough to puzzle out many book titles and store signs, and I can read short blocks of text with the help of my dictionary, but the real pain was writing each new character out about 100 times. Many years of computer work has left me with both RSI and a lack of “pencil stamina”.

So I switched workbooks. Instead of the solid but strenuous A Guide to Writing Kanji and Kana, I’m now using the Basic Kanji Book. Con: less repetition might make for sloppier handwriting. Pros: less repetition makes my hands happier, it includes reading and writing exercises that put each character in context, and, perhaps most importantly, there’s almost no Rōmaji; it’s assumed from the start that you’ve mastered hiragana and katakana.

With this book, I very quickly learned that my ability to write the characters I had learned degraded rapidly. Even some kana required conscious effort to remember, despite my ability to read them. So, switching workbooks has helped me out even more than I originally expected.

For additional practice, I went back to Level I in my Rosetta Stone courseware and switched to the writing exercises. It doesn’t support a real Japanese Input Method, but it does have a very good sentence-assembly drill, sort of a Kanji Scrabble quiz (see a picture and hear a phrase that describes it, then select the right characters to transcribe the phrase from a set of tiles). It’s quite effective.

The only problem with it is that they don’t use your platform’s native font rendering, so you’re stuck with bitmapped fonts at specific sizes, and even at the largest size, it’s difficult to differentiate between 一 and ー on the tiles. Yes, they’re different, and yes, the software will beep haughtily at you if you pick the wrong one.

Is it Engrish if they just didn't notice?

People familiar with Adobe PostScript will recognize the source of this label misprint.

How I'm trying to learn Japanese

Between my long-standing interest in anime and my on-and-off interest in Japan, I eventually became motivated to acquire at least a working knowledge of the language. Unfortunately, I know from long experience that I don’t do well in a traditional classroom setting (last I checked, the buzzwords were “underachieving gifted”), and in any case my rather irregular work schedule would make it difficult to even try.

As a result, I started looking at the available software packages, to see if any of them had any real merit. After a few weeks, I settled on Rosetta Stone, occasionally available in stores, but mostly acquired either by mail-order, online purchase, or at one of their mall kiosks (new one just opened up at Valley Fair in San Jose, by the way). They have standalone, online, and classroom packages, a pretty good reputation, and a significantly higher price than most of the alternatives.

A lot of the other software uses romanized text instead of the real Japanese writing systems, which makes things easier for absolute beginners, but effectively cripples them in the long run. RS allows you to work with romanized text, but offers both kana and kanji as options, so that you can acquire reading skills that will actually be useful.

It does not, however, teach them. For learning the hiragana and katakana syllabaries, I used the commonly recommended Easy Kana Workbook, along with LanguageBug’s free Java flashcards for cellphones. I went through approximately half of the RS Level 1 course this way, with all dialog spelled out phonetically.

Meanwhile, I started working on kanji, using the appropriately-named A Guide to Writing Kanji and Kana. It’s slow going, due in large part to the hand cramping I developed from writing each character 100 times, but I’m making real progress, to the point where I can slowly, painfully read magazine and manga text with the help of The Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Dictionary (not to be confused with The Learner’s Kanji Dictionary…).

A while back, I finished my first complete pass through the RS Level 1 software, and it’s done a lot for my comprehension and reading skills. I’ve gotten less out of the voice-training feature, largely because the feedback is unclear; it’s extremely finicky about intonation and cadence, but lacks the ability to highlight your mistakes in a way that you can correct. If you don’t have a good ear for language, you could sit there for hours without making it through the first lesson. Even if you do (and, thanks to a youth spent in my father’s office in the Language Department at UD, I generally do), it may still take a while for you to figure out what kind of mistake you’re making.

For instance, I had an early tendency to fail on any phrase that included the word otokonoko, and only that one word. Why? My cadence was off. I was making some syllables shorter than others, and the waveform display didn’t show it. It finally dawned on me that I got better results with my eyes closed. Shutting out the picture and the waveform display allowed me to focus on more precisely mimicking the sample phrase.

Was it worth the cash? Yes. I get a lot more out of spoken Japanese in anime and when I shop at Kinokuniya Books and Mitsuwa Market. Spending an hour a day listening to native speakers pronounce realistic phrases that I know the meaning of has done a lot for my understanding, and seeing them written out in kanji and kana at the same time has given me some basic reading skills.

What can’t I do right now? Carry on a conversation. Write an original paragraph without a reference book handy. Software won’t supply those skills, but it can give me a decent framework to build them on top of. The Level 2 software (which, sadly, has a completely different set of native speakers, one of whom speaks in an extremely annoying staccato) will contribute further to that framework.

Is Rosetta Stone the best language software out there? Is their learning model pedagogically sound? I can’t give definitive answers to these questions. I do know that, within the limits of the supplied vocabulary, their model produces comprehension without translation. This is dramatically better than the approach used in my high-school German and French classes twenty-plus years ago, which left me with some vague recognition skills and the ability to sing Du kannst nicht immer siebzehn sein.